Editor’s Update: In the hours since we first reported this story, there have been significant developments. The University Council at the University of Georgia voted to pass a resolution which opposes the Board of Regents policy passed last fall. The policy forbids undocumented students from attending five of its top public universities. It’s a symbolic win for supporters of academically qualified undocumented students who are banned from attending UGA, Georgia Tech, Georgia State University and Georgia Health Sciences University and Georgia College and State University, schools that the Board of Regents say had admitted undocumented students in the last two years. Regents spokesman John Millsaps told CNN while the regents have no plan to revisit the issue, they are not preventing undocumented students from getting an education. Millsaps says there are 30 other public institutions in the University System of Georgia that they can attend. He said the regents passed the policy amid growing public concern that undocumented students were taking limited seats away from qualified citizens and legal immigrants. He emphasized the regents have no plans to change the policy.

Every Sunday, in an unmarked building, in an undisclosed location in the college town of Athens, Georgia, a group of students quietly gather in secret. They are aspiring professors, diplomats and engineers who have been banned from Georgia’s top five public universities.

But here, in this donated space, it is safe to study.

Undocumented students attending class at Freedom University

Undocumented students attending class at Freedom University

This place is calledFreedom University. It has one classroom and four professors, scholars who’ve taught at the likes of Amherst, Harvard, Emory and Yale, who are teaching here, on their days off, without pay.

Their students are undocumented. They have nowhere else to go and no one else to teach them.

The American Dream

Keish grew up in South Korea. She remembers the harsh education regimen in her home town of Seoul. Classes Monday through Saturday. After-class academic programs every day. Keish and her fellow students in Seoul were basically at school from 8 in the morning until 8 at night every day except Sunday.

It sounds like a much more ambitious education system than in the United States. So how is it that Keish’s parents, who lived an upper-middle-class life in Seoul, her father earning enough money as a salesman to enable her mother to stay at home — how is it that such a couple would move to America with one thing in mind: their children’s education?

“My parents wanted me to have the freedom to learn what I wanted to learn and to pursue my interests. To do whatever I want in any field. In South Korea, students are expected to go through their academics, graduate from college, and enter office life where it’s safe,” says Keish. “My parents wanted me to have more opportunity, they wanted me to have the American Dream,” she says.

And so, when she was 10, with no English except the words “mom, dad, and maybe tiger,” Keish and her family moved to America. A low-income apartment complex is where they settled down in an immigrant community outside Atlanta.

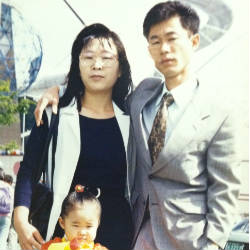

Freedom University student Keish and her parents in South Korea.

Freedom University student Keish and her parents in South Korea.

Her mother became a seamstress. Her father works at a flea market. They got tax I.D. numbers, which the government routinely gives to immigrants, and paid their taxes. CNN was shown the documentation for that.

They pushed their daughter to excel at school. Keish says it only took her about two years to become fluent in English. As for her undocumented status, she says her schools never found out. She lived with the secret.

Keish excelled in many aspects of school. She was not a straight-A student. B-plus was her average, she says. Her favorite subject was literature. She became captain of her high school debate team.

And she kept her secret. She was nominated to participate in the Governor’s Honors Program, but without a Social Security number, fear prevented her from pursuing it.

She was chosen to participate in a model United Nations trip to New York. Again, fear of being caught kept her from flying. “Many, many missed opportunities,” she says. “I was scared.

The ban

Keish graduated from high school two years ago. The timing was bad. The U.S. economy was already in a terrible state. Then the State of Georgia Board of Regents would soon alter its admissions policy to prevent the admission of any undocumented student as long as there is a single academically qualified American applicant or legal immigrant who has been turned away.

The policy, in effect, prevents the admission of any undocumented students from being admitted to the top five public colleges in the state. A spokesman for the Board of Regents told CNN the policy change was not about money. Undocumented students actually pay three times more than what Georgia residents pay. The regents said it’s an equity issue. Some argue that in these tough times, every available spot should be reserved for people who are in the United States legally.

The news was a blow to Keish. Her eyes welled up with tears as she remembered the moment she realized her American Dream was fading away.

“I fell into a deep depression. I hated myself,” she says, “because I looked back on grades and scores and thought every night and every day that I could have tried harder. Maybe I should have gotten a 4.0 and then I could have gotten into a prestigious Ivy League school. I was ashamed I didn’t try harder. I shut myself away from the world for a long time.”

But she did not quit.

The birth of a school

The moment the Regents passed the ban, a small army of students, scholars and community activists jumped into action. Lorgia Garcia-Pena, Professor of Spanish and Latino Ethnic Studies at the University of Georgia, was among the first.

She says they started with only an idea, “but no money, no building or supplies, we had nothing but our human resources and we had ganas.” (Ganas means desire in Spanish). As word spread, “overnight the books poured in and people in the community said you can have your classes here,” says Professor Pamela Voekel, a colleague of Garcia-Pena’s.

Professor Pamela Voekel hands out text books to Freedom University students

Professor Pamela Voekel hands out text books to Freedom University students

Then they came up with the name, Freedom University, in honor of the Freedom Schools in the Deep South that were developed during the civil rights movement to educate people who were excluded from the education system because of segregation.

“We borrowed the reference with respect and as homage to the people who had the same courage as our students,” says Bethany Moreton, a history professor.

Linda Lloyd, director of the Economic Justice Coalition in Athens, supports the new school. Her perspective is shaped by her memories growing up in the segregated South where she was one of six black students in an otherwise all-white elementary school. The black students often didn’t have textbooks. She says she remembers the sting of discrimination — and feeling that quality education was only for a certain few.

While others say this restriction on illegal immigrants is a matter of equity and fairness for U.S. citizens, Lloyd sees it as “a civil rights issue because it reminds me of the same issues that African-Americans were struggling with in the ’50s and ’60s.” Lloyd noted there was once a time when black people were not considered U.S. citizens.

As word spread about Freedom University, the founders began receiving calls from university students and others in the community who offered to drive the undocumented students from Atlanta to Athens, an hour and a half away. Others organized an online book drive. Then, offers started coming in from scholars around the world volunteering to lecture at Freedom University.

The school is only a month old. It has 33 students. Eight had to be turned away because of space.

Running a school for undocumented presents certain challenges. The students worry about law enforcement, about being found out, arrested and deported. They worry about harassment by anti-immigrant activists should they discover the location of the school. The professors say they do all they can to protect the students and alleviate their fears.

Professor Betina Kaplan says she has learned about perseverance and the hunger to learn. “Our students will not get school credit for the courses, and because they’re undocumented and because of their immigration status, they will not be able to work legally afterward, but they continue to come.”

“It’s wonderful,” says Keish, “they are there because they want to learn.”

Keish, an undocumented student, participates in a History class at Freedom University

Keish, an undocumented student, participates in a History class at Freedom University

This Sunday, Keish and her fellow students will gather again, as they do every Sunday, as they wait for what they hope will be a change of policy from the Georgia Board of Regents. Today, a group of professors and members of the student government from the University of Georgia will ask the University’s Council to go on record opposing the Regents’ policy. The Council will decide whether to push for a change that once again allows undocumented students, who have the grades and the scores, to apply to the state’s leading colleges.

Keish is not waiting. She is applying to colleges out of state. On her applications, she says, she is identifying herself as undocumented. She will not keep her secret any longer.

“This is my home,” she says of America. “This is the land that nurtures my dreams, that shapes who I am right now.”