The primary spirit of the letter is clear — the United States government will assure religious freedom, giving “to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance.”

George Washington wrote those words in a 1790 letter to the the congregation of a synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island. He was hoping to reassure the congregation that the budding government of the United States would allow free expression to all religions. Since then, Jews in America have flourished.

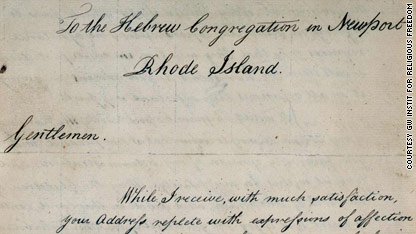

The letter is addressed “To the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, Rhode Island,” but it is kept from public view, which hurts and angers those who think private ownership defies the letter’s original sentiment.

George Washington’s letter is addressed “To the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, Rhode Island.”

George Washington’s letter is addressed “To the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, Rhode Island.”“The letter starts off to the Hebrew congregation of Newport, Rhode Island,” said Mordechai Eskovitz, rabbi of the Touro Synagogue in Newport. “It was meant for the congregation. It is addressed to the congregation.”

Eskovitz has been the rabbi of Touro for 16 years. He said the almost unanimous sentiment in his congregation is that the spirit of the letter, which he said was intended for the community and not one person, is being dishonored.

“Jews at that time were going through such turmoil and finally they found a safe haven in the United States,” said Eskovitz. “This letter, and its sentiment, is something too valuable for an individual. It is for everyone.”

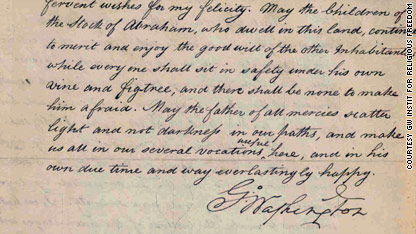

Washington signed the letter on the back. His signature gives it monetary value, but his words give the letter even more value, experts say.

Washington signed the letter on the back. His signature gives it monetary value, but his words give the letter even more value, experts say.For the last nine years, people have been unable to see the letter. It sits in a sterile Maryland office park a few hundred feet from FedEx Field. It is in climate-controlled, protective storage. However, for those who make an appointment, it is presented on a mahogany table, devoid of protective casing.

From a hallway adorned with the storage facility’s logo, workers can be seen at their computers, almost oblivious to the document in the small conference room. Though there are gadgets on desks that you wouldn’t see in most offices – a seismograph, for example – an unaware observer could mistake this place for another run of the mill office.

But this office holds documents behind lock and key that libraries and museums would love to display.

How did the letter travel from George Washington’s pen to this suburban Washington office building? The journey’s twists and turns highlight a community’s resolve to hold on to the letter’s sentiment, if not the letter itself.

From Washington to Seixas

Moses Seixas, who was president of Touro Synagogue when Washington visited Newport after the Constitution was ratified, sparked Washington’s letter. The oldest synagogue in the United States, Touro was built in 1763.

Mary Thompson, the research historian at Mount Vernon, said when Washington became president, he tried to visit every state. During his visit to Rhode Island, Washington came to Touro and was read a letter from Seixas. After he returned home, the president sent his reply.

The fact that Washington visited Rhode Island was a big deal in its own right. The fact that he visited Touro to this day astounds worshipers in Newport.

“It is a sign of how important the Jews were that they were able to meet the president,” said Jonathan Sarna, professor at Brandeis University and a pre-eminent scholar on Jewish-American history.

According to Sarna, the Jewish community in Newport was slowly dwindling at the time, losing residents to larger cities like New York and Boston. “Because the community was so small, apparently the letter (from Washington) was actually held in the Seixas family after the visit,” Sarna said.

The situation became so grim for Touro that in the early 19th century, the synagogue was forced to close. In an ironic twist, after losing people to bigger cities, Touro sent some of its scrolls and other valuables to its mother synagogue, Shearith Israel Synagogue in New York.

The letter, however, was not sent to Shearith Israel.

“You would have thought they got the letter,” Sarna said. “The letter was many times reprinted, people at the time knew it was a significant letter.”

The closure of Touro leaves a gap in the path of Washington’s letter. Touro reopened in the late 19th century, but the letter did not surface at the synagogue.

It wasn’t until the early 20th century, when a squat Jewish philanthropist began publicizing his ownership of the letter, that the trail picked back up.

From Newport to New York

Howard Rubenstein had just opened a small PR office on Court Street in New York when he was invited to meet Morris Morgenstern. Morgenstern was a public person in need of a publicist and he hoped Rubenstein would fill the job.

“I went to his office and he was a diminutive person, probably 5-2 or 5-3, very short and very lively. Tremendous energy,” said Rubenstein.

At their first meeting, Morgenstern brought up a letter he had purchased, a letter signed by George Washington and addressed to the Hebrew congregation of Newport.

Rubenstein doesn’t know how Morgenstern came upon the letter, but according to The Jewish Daily Forward and a 1951 New York Amsterdam News article, Morgenstern acquired the letter in 1949. From who and at what price is unknown.

Using the letter, Rubenstein devised a way for Morgenstern to increase his philanthropic giving. The duo turned viewing the letter into an honor given to prominent people who Morgenstern would get to meet. Morgenstern also would give the viewers of the letter $5,000, a large some of money at the time, for the charity of the person’s choice.

The plan worked.

Morgenstern and the letter were able to meet former President Herbert Hoover, former President Harry Truman and then-Sen. John F. Kennedy, as well as former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt. “The only thing I asked these people was when you greet Morris, indicate that you have read the letter and you were delighted to see it,” Rubenstein said.

Morris Morgenstern, center, showed a number of notable people his prized letter, including then-Sen. John F. Kennedy. Howard Rubenstein is at right.

Morris Morgenstern, center, showed a number of notable people his prized letter, including then-Sen. John F. Kennedy. Howard Rubenstein is at right.According to Rubenstein, Harry Truman even hugged Morgenstern when they met and said, “I have heard all about your letter and am so excited to see it.”

After the duo stopped publicizing the letter, Rubenstein lost touch with Morgenstern. Rubenstein said he looks back on those days fondly.

“It was a very exciting time for Morris and for the country, because the publicity that it generated about a country opposed to bigotry was very important,” said Rubenstein. “I thought I was doing an important thing in those days.”

Morgenstern also believed the letter he owned was important. According to Rubenstein, Morgenstern cherished the letter so much, he would sleep with the framed letter under his bed at night and would take it almost anywhere he went. Rubenstein called the relationship “erotic.”

In 1957, Morgenstern loaned the letter to B’nai B’rith International, according to Dan Mariaschin, executive vice president of the organization.

Why Morgenstern made the loan is unknown. He died in 1969.

New York to suburban Maryland

Mariaschin said former B’nai B’rith’s president Phillip Klutznick secured the loan for the organization’s museum in Washington. Klutznick was a well-known Jewish leader and Jimmy Carter’s secretary of commerce. Mariaschin says it was that relationship that cemented the loan.

When CNN contacted the Morris Morgenstern Foundation, Paul Goodnough, the foundation’s accountant, said he didn’t think this “very private family” would like to talk about the letter.

“If they reach out to you, they want to talk. If they don’t, it is a no comment,” Goodnough said.

The Morgenstern Foundation did not contact CNN.

B’nai B’rith displayed the letter from 1957 to 2002 in its Washington museum, Mariaschin said. The organization downsized in 2002, moving to a smaller office on K Street, an office with no street level location for a museum. Though the organization maintains a reservations-only gallery in its current space, the letter’s unique storage needs were too much for an office environment, so B’nai B’rith contracted Artex, the warehouse in suburban Maryland, to store the letter.

“We are in active discussion now with several institutions about partnering in terms of the display of this very nice collection that the Klutznick museum has,” said Mariaschin.

Since the letter went into storage in 2002, a number of prominent libraries and museums have asked to display it for B’nai B’rith and the Morris Morgenstern Foundation.

Among them was the Library of Congress, which asked to display the letter during a 2004 exhibit celebrating the 350th anniversary of Jewish life in America. Jennifer Gavin, director of communications at the Library of Congress, said the letter was requested but not obtained.

“It’s not unusual for institutions like the library to reach out to owners of rare documents for such purposes and find that, for a variety of reasons, the loan can’t be accomplished,” said Gavin.

Sarna helped advise the Library of Congress’ celebration of Jewish life. He said the people he worked with were astonished by the rejection.

“Usually people would die just to be invited to display their property,” Sarna said. “If the Library of Congress wanted something of mine, they would have it the next day with insured mail.”

This part of the letter’s history distresses Jane Eisner, editor of the Forward. The unwillingness to display the letter, she says, hides not only a critical piece of Jewish American history, but also of American history in general.

“We have flourished in America and it is largely because we have been allowed to,” said Eisner. “That spirit of tolerances and acceptances was expressed so beautifully by Washington in that letter.”

But where is the letter’s rightful home?

Bernard Bell has become disillusioned with Touro Synagogue over the years. Twenty-five years ago, he began a scholarship program at Brown University in honor of the synagogue. Before that, he was a member.

Bell is outspoken, and without much prodding he will bluntly tell anyone who listens that he believes the Morris Morgenstern Foundation does not rightfully own the letter.

“The possession of the letter was in the hands of the congregation and I don’t believe at the time that it was sold that anyone had the right to sell it,” Bell said.

Bell said the majority of Newport Jews, especially those who have been around for quite awhile, agree with him. He said the problem is, “There is nobody in the congregation that I am aware of that has the guts to go after that letter.”

To Bell, the power of the letter is not just its historical significance, but also its monetary value.“It is the most valuable piece of work outside of the synagogue that we have. No one had the right to sell it and it shouldn’t sit in the warehouse,” Bell said.

The letter has not been valued lately, but Dana Linett, a colonial documents expert, said the letter could be worth millions.

“I would think that the Touro is a million-dollar or better, it might bring multiple millions, depending on the condition and how it reads,” Linett said.

Linett said he has seen documents like the Washington letter have what he called a “runaway sale.” When a group so identifies with the document, the sale at auction could defy actual valuation, he said. The symbolic power of the letter could mean more than money. In cases like this, Linett said he has seen documents once valued at $1.5 million shoot up to $8 million in a matter of minutes at auction.

“It is a national treasure. That is what this letter is in its truest sense,” Linett said.

Linett is not alone in valuing the letter’s sentiment. John L. Loeb Jr. has put his money behind that opinion.

Loeb spent about $12 million to found the George Washington Institute for Religious Freedom, which opened in 2009. Since first reading the letter, Loeb said, “I have been deeply interested that everyone gets to know it. It is one of the great letters about religious freedom that has ever been written and perhaps the earliest by a head of state.” The institute, near Touro in Newport, serves that purpose by displaying a copy of the letter.

Newport is home to the Touro Synagogue, the Loeb Touro Visitors Center and the George Washington Institute for Religious Freedom.

Newport is home to the Touro Synagogue, the Loeb Touro Visitors Center and the George Washington Institute for Religious Freedom.Loeb speaks excitedly about the letter’s sentiment. However, Loeb, a former ambassador to Denmark who has committed most of his philanthropic life to the letter, seems reflective when he talks about displaying only a reproduction.

Loeb said though he would like to house the original letter, it is the sentiment that is more important. It is the sentiment, not the physical letter, that moved him to build the institute.

“To me, the uniqueness of America is the acceptance of everybody,” Loeb said. “That is what made America possible. And this letter symbolizes what America is all about.”